A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

‘Tis the season to be jolly, kiss under holly, and have a psychotic break of melancholy. Christmas can often be paradoxical in how much people genuinely love the holidays by counting down the days as early as July or putting up trees well before little kids in costumes harass their neighbors for candy. Others approach the festivities with dread, reminiscing of long-dead loved ones and family traditions, or generally being a grouchy old humbug. For those unfortunate individuals in the latter category, the Christmas season heralds a harbinger of mental illness–a cyclical wave of psychotic woe canopied by snow and the feverous delusions of a Grinch-like low. And also an epidemic of rhymes.

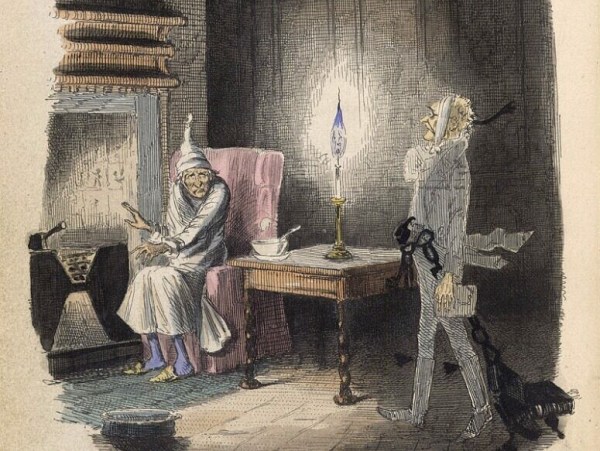

‘Christmas Psychosis’, a phenomenon largely felt by those like me working in mental healthcare who notice a surge of crisis beginning in late November through to the new year, is the idea that something about this time of year triggers a wave of renewed psychotic symptoms in a population already prone. Perhaps one of the most famous iterations of this case is the fictional Scrooge finding himself haunted by hallucinations of ghosts representing the past, present, and future Christmases. A Christmas Carol is a seasonal classic, many of us grew up seeing it performed in theaters, and Charles Dickens was no stranger to depicting bouts of psychotic depression in his works (Garratt, 2022). But is the idea that psychosis comes but once a year, with such prevalence, we ought to leave it out a tray of cookies, one that’s based in reality?

Since at least the 1950’s, some psychoanalytic thought has suggested that neuroses around Christmas time were because the celebration was focused on the birth of Jesus, the ultimate God’s favorite child over the rest of us, and that this brought up unresolved feelings related to competing against our siblings (Boyer, 1955). As the older and obviously favorite child who was Christmas-gifted the PlayStation over my brother, I can’t say that I’ve ever felt triggered by Jesus for having his own holiday. Though there is some evidence to suggest that being around Christmas-y things can lead to a negative psychological impact on people who are not religious or participating in festivities, who may already be dealing with feelings of exclusion (Schmitt, et al., 2010). There is even a bizarre phenomenon known as White Christmas effect, where researchers use Bing Crosby’s version of the song to study participants’ capability of auditory hallucinations. In traditional versions of the study, the song would be played briefly, and then white noise would be played for the participants. They would be asked if they could hear the song through the white noise, with around half of the people saying they could, and over a majority of schizophrenic participants stating the same. But many researchers suspect the general population may be reporting hallucinations because they were expected to or because they may already be prone to flights of fancy, rather than because songs about Christmas cause psychosis (Scott & Leung, 2025). Though I certainly do feel like losing my mind when Christmas songs are played on retail loops before Thanksgiving.

But surely there must be an uptick of emergency room visits when it seems like everyone and their dog spends the majority of winter slightly unhinged. That, too, appears difficult to determine. Some studies show there certainly does seem to be an increase in ER visits for psychiatric reasons during the holiday season (Halpern, et al., 1994), but others show that there may even be less utilization of the ER during the holidays for mental health, despite what we assume about psychosis season (Schneider, et al., 2023). However, there does appear to be a noticeable uptick in miserable feelings around Christmas and alcohol-related deaths, with the period after the holidays showing the real increase in psychiatric hospitalizations (Sansone & Sanson, 2011).

So, basically, Christmas Psychosis is all in our heads. Fitting perhaps, but not an unjustifiable conclusion given how crazy things get around this time of year. I will say this, however, if there is any truth to the matter of psychosis for Christmas, maybe watch how much nutmeg you’re putting in your eggnog! That DOES cause hallucinations (Ehrenpreis, et al., 2014).

Fact Check it, yo!

Ehrenpreis, J. E., DesLauriers, C., Lank, P., Armstrong, P. K., & Leikin, J. B. (2014). Nutmeg poisonings: A retrospective review of 10 years experience from the Illinois Poison Center, 2001–2011. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 10(2), 148-151.

Garratt, P. (2022). Household ghosts and personified presences. In A. Woods, B. Alderson-Day, & C. Fernyhough (Eds.), Voices in psychosis (p.153). Oxford University Press.

Halpern, S. D., Doraiswamy, P. M., Tupler, L. A., Holland, J. M., Ford, S. M., & Ellinwood Jr, E. H. (1994). Emergency department patterns in psychiatric visits during the holiday season. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 24(5), 939-943.

Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2011). The Christmas effect on psychopathology. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(12), 10.

Schmitt, M. T., Davies, K., Hung, M., & Wright, S. C. (2010). Identity moderates the effects of Christmas displays on mood, self-esteem, and inclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 1017-1022.

Schneider, E., Liwinski, T., Imfeld, L., Lang, U. E., & Brühl, A. B. (2023). Who is afraid of Christmas? The effect of Christmas and Easter holidays on psychiatric hospitalizations and emergencies—Systematic review and single center experience from 2012 to 2021. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1049935.

Scott, M., & Leung, T. T.-C. (2025). I’m whispering a white Christmas: masking relations in hallucinatory speech. Language and Cognition, 17, e71.